Unwarranted: Reconsidering the Air Force Warrant Officer

The Air Force is faced with a long-standing conundrum — not enough pilots, particularly fighter pilots. The causes of the shortage are longstanding, and have defied easy or quick solutions. The introduction of light attack aircraft (if that ever happens), offers potential to solve part of the problem by increasing the number of available cockpits. Oddly enough, the pilot shortage is exacerbated by too few so-called “absorbable cockpits” because they can absorb new students and turn them into experienced aviators. But even increasing the supply of aircraft is not enough. The Air Force also needs a wider training pipeline to provide students in the first place, and an accessions policy that ensures it can get people who will become aviators into the service in the first place. That is proving particularly challenging using traditional methods.

Making conditions worse is the emerging focus on great-power conflict. The resurgence of Russia and the emergence of China as a modern military power will prove challenging for the Department of Defense, but particularly for the Air Force. The service’s tip of the spear relies heavily on trained aviators who take time to train and develop and cannot be produced rapidly at need. Furthermore, a growing emphasis on distributed operations to frustrate adversary targeting of airfields will likely increase the demand for air-delivered logistics, and thus the demand for pilots. Unrepentant airpower advocates, we have recently recommended an increased use of aviation capabilities derived from civil aviation, including light airlift and utility aircraft.

It should be possible to roll together several challenges and address them with an integrated solution. There is an option that the Air Force has long avoided for cultural reasons: warrant officers, and particularly warrant officer aviators. This grade of specialist, which the Air Force discarded decades ago, offers a possible solution not only in aviation but in other areas (such as cyber) where specific technical expertise is desired. Alone among the services, the Air Force has failed to capitalize on the opportunities provided by a warrant officer force. The Army has had aviation warrant officers, in their current form, since 1949, but the Air Force phased its own out without replacement.

Taking our cue from the early years of World War II, we believe that the Air Force can roll together civil aircraft, civil aviation training, and an aviation warrant program to help solve our pilot shortage while expanding airpower capabilities. Our proposal is intended to enhance the effectiveness of deployed forces, increase the pilot supply, provide a strategic reserve of trained aviators (the Civil Reserve Airman Force), and provide a long-term source of pilots better postured for transition to civil airlines than our fighter pilots.

The History of the Warrant Officer

Warrants occupy the space between enlisted personnel and commissioned officers, blurring the lines between both. In order to understand the warrant officer, we need to sail back in time: Warrant officers originated with the Royal Navy in the age of sail. The officers on a warship held their commissions from the monarch. Warrant officers, on the other hand, were professionals who did not hold a commission, instead holding warrants granted to technical specialists necessary to ship operations. These seamen were often “board-certified” and had likely served an apprenticeship. Literacy was the sole common requirement and warrants were not considered “gentlemen,” which was a necessary prerequisite for an officer’s commission.

Wardroom warrants held their warrants from the Navy board and shared access to the wardroom and the quarterdeck. These included the sailing master (navigator), surgeon, chaplain, and the purser (quartermaster), who was in charge of clothing and provisions. Standing warrants were permanently assigned to the ship, and included the boatswain (bosun), gunner, and ship’s carpenter. Lower-grade warrants held their warrants from the captain, and were essentially petty officers promoted to warrant rank. These officers were the master-at-arms, sailmaker, caulker, armorer, ropemaker, and cook. All except the cook were tradesmen essential to maintaining a fighting ship.

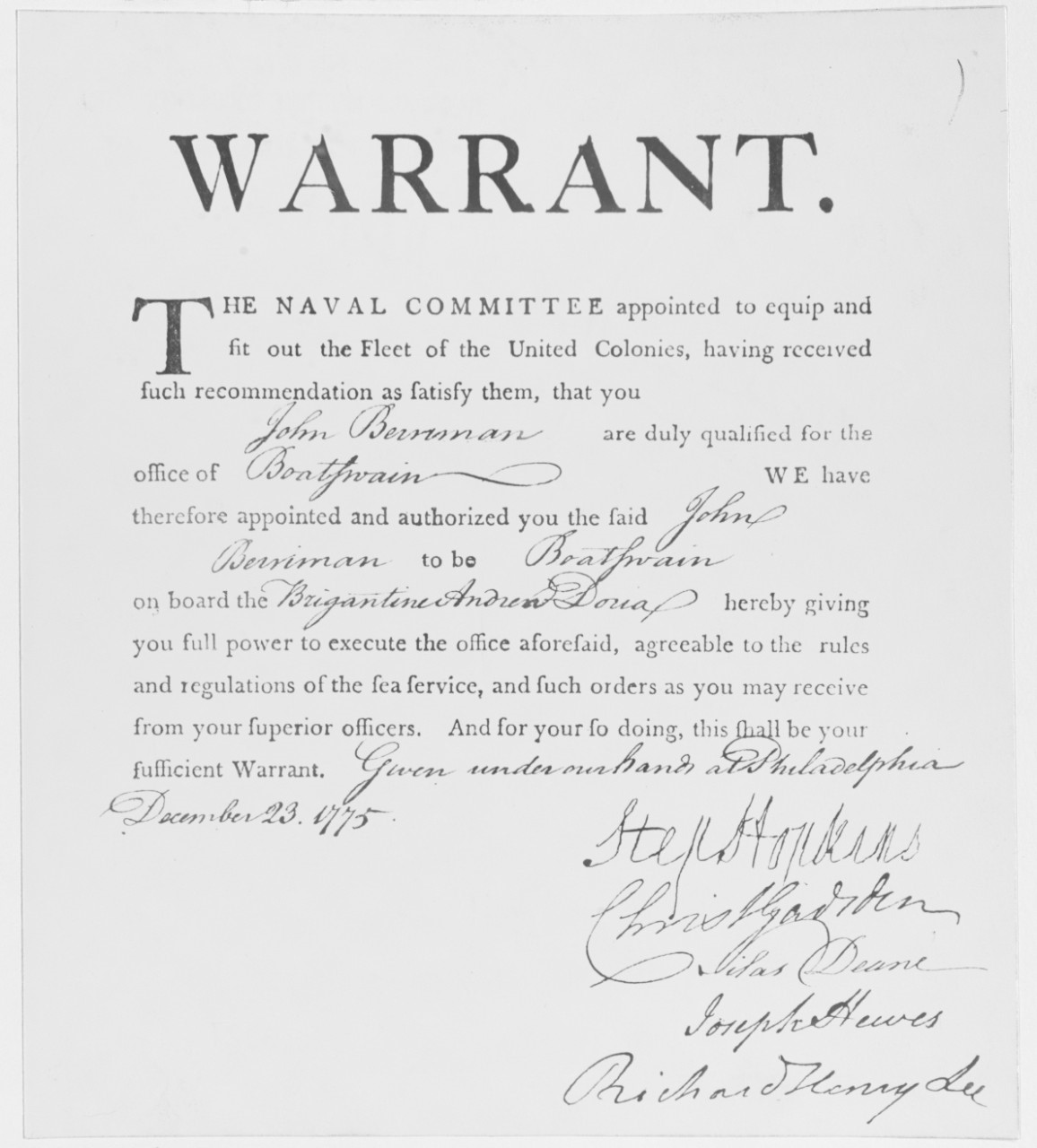

The U.S. Navy’s first warrant was John Berriman, the boatswain of the USS Andrew Doria, in late 1775. Boatswains, gunners, carpenters, and sailmakers were early American warrant officer positions, with mates, clerks, machinists, and pharmacists added later. The warrant officer ranks have survived in the Navy until the present day precisely because they fill a need — creating and maintaining a stable pool of specialists who retain that specialty throughout their career.

Figure 1: Warrant appointing John Berriman as boatswain of the Andrew Doria. (Naval History and Heritage Command)

Aviation Warrants

The Army’s warrant officers were created much later, in 1901, to crew minelayers belonging to the coastal artillery branch. The branch was formalized by Congress on July 9, 1918 — the official birthday of the Army’s Warrant Officer Corps. Aviation warrant officers are a later creation, and the Army tried several other methods on the way. As early as 1912, the Army Air Corps had trained enlisted pilots, or “flying sergeants,” who received staff sergeant rank with their wings. But the majority of aviation cadets had two years of college, making them officer candidates. As war loomed in late 1941, Brig. Gen. Carl Spaatz directed a reconsideration of the college requirement, which he believed to be archaic because it placed “too much emphasis on formal education which may mean nothing and…no emphasis on native intelligence which may mean everything.” In 1942, the “flight officer” rank was created for Army aviators, partly because of concerns that mixing enlisted and officer aviators would muddy chains of authority, and put commissioned officers in the position of taking orders from enlisted pilots. Flight officers, who were essentially “third lieutenants,” were paid as warrant officers. Enlisted pilots did fly all kinds of aircraft, including fighters, and some became aces, but their overall numbers were small. The flight officer rank neatly solved a host of problems, but did not long survive the war. All flight officers were either commissioned or discharged by war’s end. The Air Force did inherit warrant officers when it became a separate service, but saw no use for them, and phased them out.

Ironically, the Army did not do away with them, re-establishing aviation warrant officers in 1949. The Army started using warrants to fly helicopters in 1951, a practice that continues today, when aviation warrant officers make up more than half of the flyers in most helicopter squadrons. Indeed, the Army has over 10,000 warrant officers in the aviation branch, many of whom are pilots. Warrant officer grades number five, from W-1 (warrant officer) to W-5 (chief warrant officer 5).

Why not the Air Force?

Figure 2: An Army C-12 Huron, the military variant of the Beechcraft 200 King Air. (U.S. Army)

A Parallel Training Pipeline

Today’s Air Force pilots undergo roughly two years of training at significant expense. Pilot candidates for manned aircraft are all commissioned officers with a bachelor’s degree who attend Undergraduate Pilot Training. By the time their 10-year commitment is up, they are in high demand by civil airline fleets, and retaining these trained and experienced individuals is an ongoing challenge. The Army’s aviation warrants fly the C-12 along with attack and utility helicopters. Warrant candidates must be 18 to 33 years of age, have 12 or fewer years of military service, and do not require a college education. The aviation warrant officer program is highly competitive and produces aviators with a one-year aviation training program.

In our other articles, the authors proposed using civil training programs for aircraft that have civil counterparts. The Army’s use of warrants provides an example of this — the Army’s C-12s are Beechcraft King Air 200s, widely used in civil aviation. Army warrants go through the same aviation training program as commissioned officers. Our previous proposal for light airlift aircraft such as the Series 400 Twin Otter (UV-18C) would strain the pilot force as it currently exists — but not as it might exist. As in World War II, it could be possible for military pilots to go through the civil training program, emerging with civil certificates and qualified to fly military aircraft derived from civil designs. We call this proposal Civil Pilot Training, or CPT.

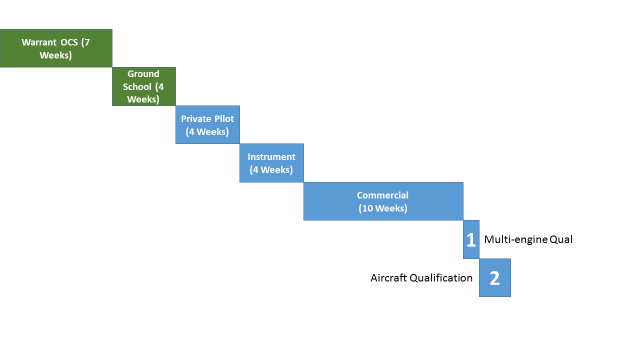

The authors believe that CPT can be accomplished at a single location in 30 weeks from the day a warrant officer candidate hops off the bus to the day she gets her aircraft qualification. We designed a copy of the Army’s program that had the same warrant officer candidate school (7 weeks) and then melded a Part 141 FAA-approved syllabus with some additional training (in aerospace physiology, flight regulations and weather) that would be common to military pilot training. At the end of CPT, an aviation warrant would have dual engine, instrument and commercial qualifications, and have received a basic qual in a single airplane (perhaps the UC-18 Twin Otter). She would have logged slightly over 200 hours of flight time, all in civil aircraft.

Rather than graduating UPT at 24, aviation warrants might finish CPT as young as 19, having substituted civil pilot training for college. In our vision, the warrant officer pipeline would feed remotely piloted aircraft and military derivatives of civil designs, such as the C-21, UV-18, U-28, and MC-12.

Figure 3: Aviation Warrant Training Program. (Notional design by the authors)

The cost of producing an Air Force pilot today ranges from $600,000 to $2,600,000 depending on the type of aircraft flown, with fighters being the most expensive. On the other hand, the cost of training to become the pilot of a regional airline jet — similar to a Twin Otter — is more like $70,000, though that leaves the pilot nearly 1,000 hours short of the hours required by Congress to become a pilot at a major airline. The student must then pay another $200,000 getting enough flight time to be accepted into airline employment. A warrant officer student would have that burden paid for by the government — using existing Part 141 flight schools rather than a military flight school. At the end of CPT, aviation warrants would incur a five-year commitment in active service, plus another five in the reserves.

After the five-year commitment is up, the aviation warrant is a CW2, and is approaching or has reached the 1,500 hour mark required for entry into the major airlines. She is around 25 years old, has been flying for six years, just met a promotion board for CW3 and may have a college degree. She earns $4,291 per month in base pay (about 72 percent of what a commissioned officer with the same time in service makes). At any point after getting wings and a four-year degree, she has been eligible to apply for Officer Candidate School and the traditional UPT track. Alternately, she can go to the airlines, retaining a reserve commitment, or re-up for another four years of active service. Indeed, the warrant officer may feasibly follow a “fly-only” career path, without the management responsibilities of the officer corps. In times of emergency, she is part of a trained, experienced corps of aviators who can be used in their existing specialty or trained up in a traditional military program much faster than new accessions.

The long reserve commitment allows the Air Force to keep track of its investment to ensure the pilot remains current and qualified, and constitutes part of a Civil Reserve Airman Fleet, to be called upon in time of need. At the same time, the active-duty commitment (half the length of the UPT graduate) also provides civil-trained aviators to the airlines that could reduce demand for the much more expensive graduates of military UPT. We think it likely that the short active-duty commitment will be attractive to individuals who do not want a military career, but cannot afford the self-funded airline career path. The Air Force pays for the training and flight time, but certainly gets its return on investment (and more) in return.

As a bonus, the Air Force saves on personnel costs, because warrants occupy an intermediate pay scale commensurate with their intermediate rank. Since warrants are not as expensive as officers, and (on average) start service four years younger than their commissioned counterparts, the Air Force will incur lower pay and benefits costs, (presumably) lower health care costs, and lower retirement burdens. The warrants gain a rapid on-ramp to an aviation career path, access to the brand-new blended retirement plan, and flying experience paid for by the government.

The Demand

This particular model requires a demand signal. The design outlined above, with today’s force structure, would only have flying opportunities for a few aviators, although warrants destined for other career fields would not be so limited. But in order for the aviation warrant officer to have a career path, the Air Force would also have to embrace our proposals for a civil-derived aircraft fleet for light airlift and special mission aircraft. Fleshing out an example from Uplifted, the authors advocated for a fleet of Twin Otters, assigned to the Air Division, to support distributed operations in Europe.

Twin Otters would be based in the United States for training and prepositioned forward in Europe. CPT pilots and small detachments of Twin Otters would be directly attached to stateside fighter bases and could enable those units to train for “adaptive basing” to disperse for survival, matched with Multi Domain Command and Control to enable “rapid aggregation” at the point of need. In time of conflict, the Air Division would deploy forward without its training airlift but with all of its pilots, “rounding out” the forward-deployed light airlifters with the higher crew ratio needed for high intensity ops.

Figure 4: Royal Canadian Air Force CC-138 Twin Otter waits on runway after delivering supplies and personnel to “Ice Camp Skate” in Alaska, during ICEX 18 on March 5, 2018. (U.S. Navy photo by A1C Kelly Willett)

The Complete Vision

This article stitches together much of the vison that we have been advocating for the past few months. We intend to draw together a newly capable combat formation (the Air Division) with its own light airlift capabilities, an operations concept that is designed to counter Russian grey zone activities in Europe, and a pilot training architecture that will expand the Air Force’s pilot supply while providing a strategic reserve. We propose to do this with programs and aircraft that are available today, at a fraction of the cost of military aircraft. The complete concept includes:

- A reconstituted, broadly capable Air Division as a combat formation

- Civil aircraft purchased for light airlift and utility roles

- Expanded air operations in the grey zone

- Use of civil training to remove pressure from the military pilot training program to man civil-derived aircraft

- The Civil Reserve Airman Fleet/Strategic Reserve

- An aviation-focused warrant officer program

The interlocking pieces are intended specifically to provide the Air Force with a combat capability to counter a broad range of hostile actions that the Russians are already employing in Europe. We intend to make distributed operations more supportable and therefore more employable, and we believe that by returning to pilot training methods that have proven successful in the past, we can overcome a persistent pilot shortage that shows no sign of abating. In short, we advocate returning to an inclusive vision of airpower that incorporates expensive, purpose-built, high-end aircraft, while not limiting ourselves entirely to those machines as our sole measure of airpower effectiveness. Finally, we hope to capitalize on a uniquely Western civil aviation enterprise that is not duplicated in either Russia or China.

Col. Mike “Starbaby” Pietrucha was an instructor electronic warfare officer in the F-4G Wild Weasel and the F-15E Strike Eagle, amassing 156 combat missions over 10 combat deployments. As an irregular warfare operations officer, Colonel Pietrucha has two additional combat deployments in the company of U.S. Army infantry, combat engineer, and military police units in Iraq and Afghanistan. He is currently assigned to Air Combat Command.

Lt. Col. Jeremy “Maestro” Renken is an instructor pilot and former squadron commander in the F-15E Strike Eagle, credited with over 200 combat missions in five combat deployments. He is a graduate of the Weapons Instructor Course and is currently an Air Force Fellow assigned to Air Combat Command.

The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Air Force or the U.S. government.